In a parallel timeline, the PlayStation might’ve been just another add-on. A CD-ROM sidekick for Nintendo with no identity of its own. But instead, like many a great antihero, it wasn’t the one to rebel first. Nintendo was. Ghosted by its first love, it went solo. And in doing so, it embraced an attitude that was something rare in the world of electronics: a genuine outlaw, out for revenge.

You could almost call the PlayStation a console with detachment issues. Born from a very public breakup between Sony and Nintendo in the early ’90s, the PlayStation was forged in corporate betrayal. At the 1991 CES trade show, Nintendo blindsided Sony by announcing it would be partnering with Philips instead on a CD-ROM hardware feature for their new console (the Nintendo64). It was a pixelated soap opera. Sony, wounded but not defeated, took its prototype home and built the PlayStation from the ashes. The betrayal became the birthmark.

But revenge is best served plugged in. When it finally hit shelves in 1994, the PlayStation didn’t just offer a different kind of machine—it offered a different kind of fantasy. Where Nintendo sold childhood nostalgia and SEGA leaned into speed and attitude, Sony saw the pixelated pubescent dreams of teens becoming twentysomethings. They weren’t being served. The industry was still stuck in a rumpus room. Sony saw the vacuum—and lit a match.

Games for Grown-Ups, and Grown-Ups in Games

PlayStation’s launch wasn’t just technical; it was spiritual. It was a rejection of the old guard. The system's grey, angular design looked like alien tech compared to the playful curves of Nintendo’s consoles. But it was the games that really carved out its outlaw image. Gone were the bouncy plumbers and hedgehogs. In came the criminals, the outcasts, the freaks.

Grand Theft Auto, initially a top-down, chaotic sandbox of crime and nihilism, found its home and audience on PlayStation. Fear Effect, with its cel-shaded noir aesthetic and sexually fluid protagonists, was another slap in the face to the safe, kid-friendly status quo. These weren’t just games—they were provocations. And, naturally, they sparked outrage. American parents in the ’90s clutched their pearls and remote controls, panicked by the idea that digital thievery and pixelated promiscuity were melting their children's minds (which was later debunked). The PlayStation became the poster child for moral panic.

But this rebellion wasn’t just about edge. It was also about expression. Sony’s more open developer policy allowed space for weird, wonderful experiments. LSD: Dream Emulator, for example, was less a game and more a guided hallucination, designed by multimedia artist Osamu Sato. Inspired by his actual dream diary—and possibly a few tab drops—it was part Dadaist art piece, part nightmare simulator. It barely made sense, but it made a statement: the PlayStation was a canvas for the strange, not just a playground for the loud.

This was the seed of the indie explosion, years before it had a name. The PlayStation showed that games didn’t have to be clean, cute, or coherent to matter.

Sex, Drugs, and Loading Screens

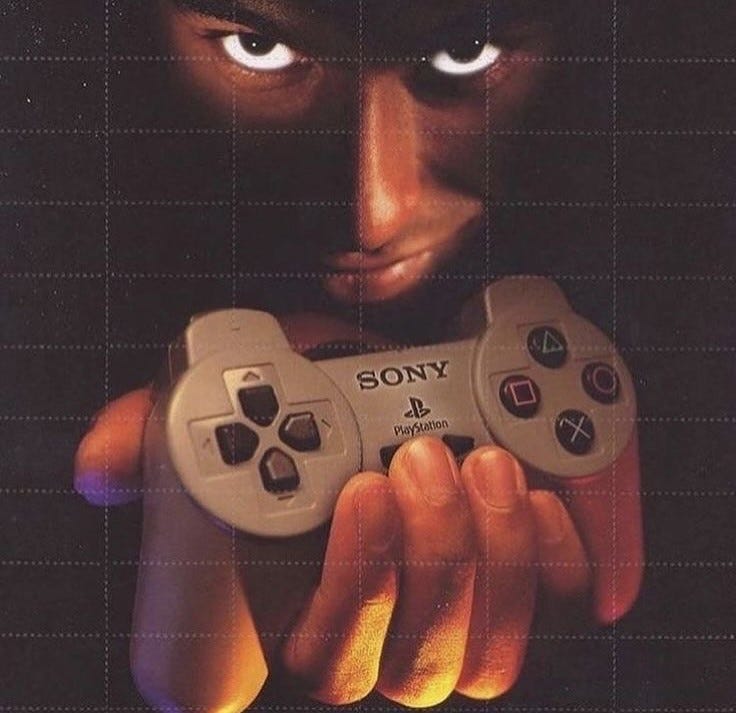

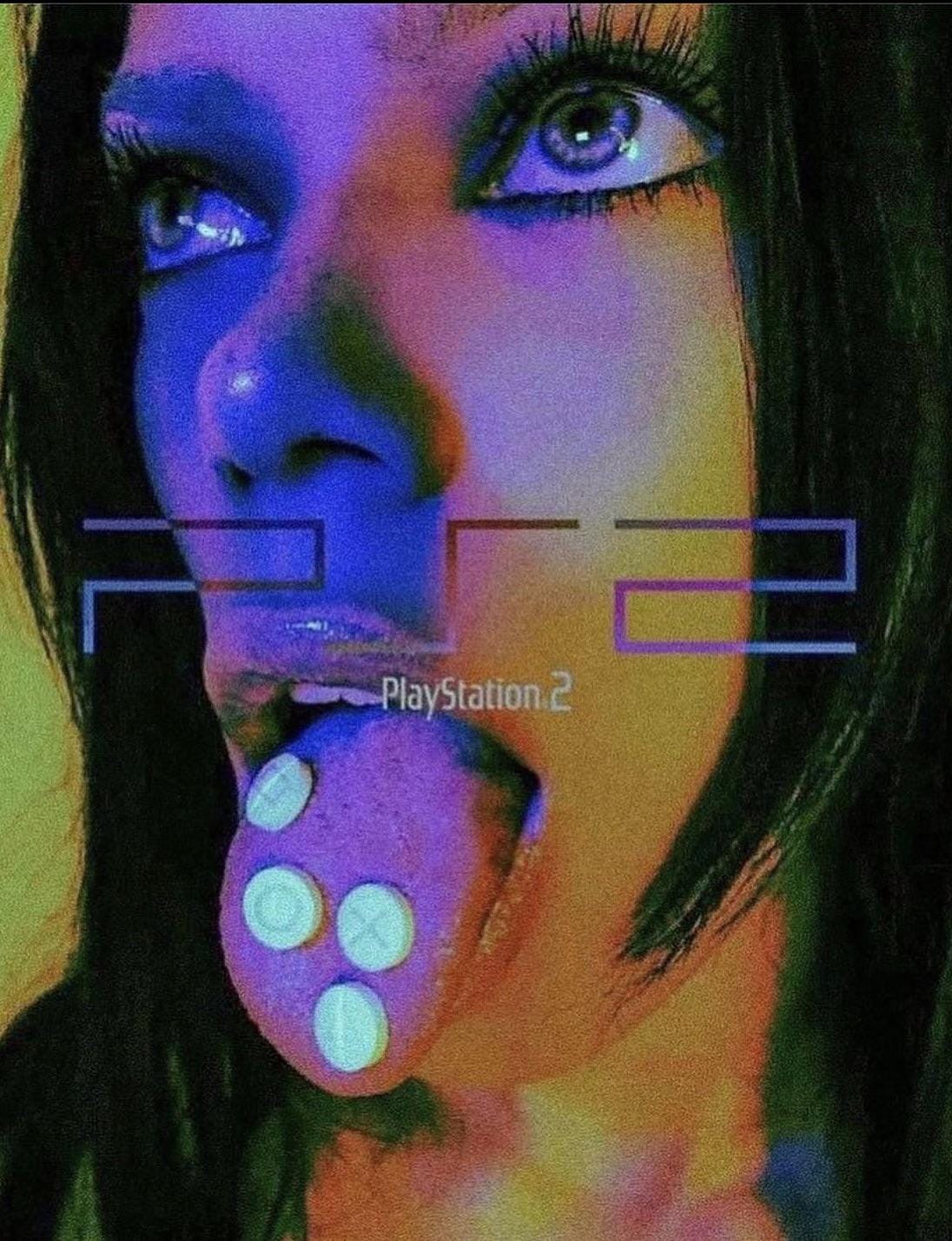

PlayStation’s rogue status wasn’t just in the games—it was in the way it sold itself. Its ads in the late ’90s and early 2000s didn’t whisper; they screamed. They weren’t shy about leaning into counterculture, using glitchy visuals, surreal storytelling, and strong suggestions of altered states. Some ads were down right Lynchian: unsettling, cryptic, oozing with subliminal anxiety. Others were punk manifestos in miniature.

One 1999 commercial featured a disembodied female head talking in a bizarre accent while the camera zoomed into her face like a bad acid trip. Another print ad promised: “Do not underestimate the power of PlayStation” next to a man seemingly mid-orgasm. These weren’t just marketing stunts—they were declarations. PlayStation wasn’t here to babysit. It was here to blow your mind.

This wasn’t just iconoclasm for its own sake—it was targeting. Young adults, freshly independent, fresh off the Super Nintendo, were craving entertainment that felt made for them. Sony delivered with ads that flirted with psychedelia, sexuality, and the surreal. It wasn't just a brand—it was a vibe.

From Console to Cultural Collab King

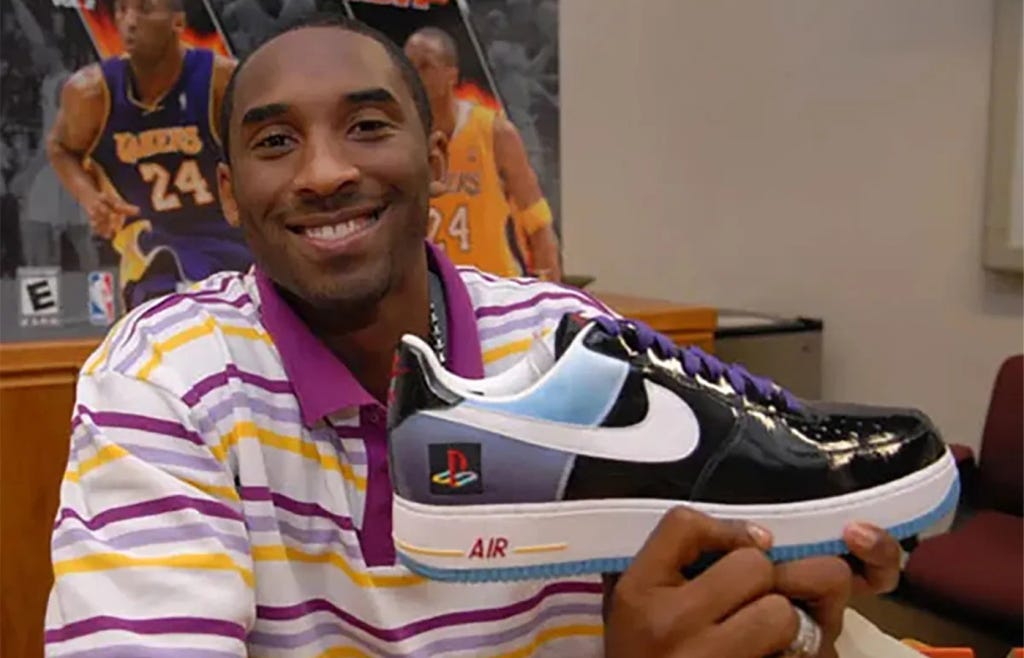

If the ’90s were about burning down the old house, the 2010s were about buying a bigger one and inviting your coolest friends over. As the PlayStation brand matured, it didn’t lose its edge—it stylized it. No longer just a rebellious teenager, it became a taste-making young adult. And like all good influencers, it started collaborating.

PlayStation’s collabs with fashion and lifestyle brands—Nike, Balenciaga, BAPE, even Parisian concept store Colette—weren’t just cash grabs. They were aesthetic extensions of the brand’s outlaw ethos. Streetwear and PlayStation were both rooted in youth rebellion, in curating identity against the mainstream. Whether on a sneaker or a DualShock controller, the PS logo became a symbol of subcultural fluency.

And this wasn’t just marketing synergy. It was legacy. The kids who grew up skipping cutscenes in Metal Gear Solid were now adults buying limited-edition PlayStation x Balenciaga hoodies for the same reason they once bought cheat code books: because it felt like being in on something.

Still Not a Role Model

Now, in a gaming landscape dominated by streaming platforms, algorithmic discoverability, and AI-generated everything, it’s tempting for legacy brands like PlayStation to go corporate. To clean up. To play nice. But if PlayStation wants to remain relevant, it has to stay messy. Stay strange.

The outlaw spirit doesn’t mean always being edgy—it means always being unpredictable. It means continuing to support the oddballs, the dream emulators, the narratives too strange for Netflix. It means finding the new frontier before anyone else realizes it’s there—and making it yours.

In an age of content, PlayStation still has the chance to be culture.

And if that means getting into a little more trouble? Well—good.